di Isaac Asimov

Avevo scritto un articolo in quattro parti per il Field Newspaper Syndicate all’inizio di ogni anno per molto tempo fin agli anni ’80, pensando all’avvicinarsi del 1984, FNS mi chiese di scrivere un critica al racconto 1984 di George Orwell. Ero riluttante. Non ricordavo quasi nulla del e lo dissi – ma Denison Demac, la ragazza amabile che era il mio contatto con FNS, semplicemente mi spedì una copia del testo e disse “leggilo“. Così lo lessi e mi sorpresi meravigliato di ciò che leggevo. Ero sorpreso di quanta gente parlasse del testo in modo così spigliato, senza averlo mai letto; o se l’avevano fatto, non lo ricordavano affatto. Sentì di voler scrivere la critica solo per avvertire la gente. (mi dispiace; mi piace farlo.)

A. Lo scritto 1984

Nel 1949, un libro intitolato 1984 venne pubblicato. Era stato scritto da Eric Arthur Blair con lo pseudonimo di George Orwell. Il libro cercava di mostrare come la vita sarebbe stata in un mondo totalitario in cui il governo si mantiene al potere con la forza bruta, distorcendo la verità, riscrivendo in continuo la storia, insomma ingannando il popolo. Il mondo da incubo esisteva a 35 anni nel futuro, così che le persone di mezza età, al momento della pubblicazione del libro, avrebbero potuto constatare se avrebbero vissuto una vita normale. Io, al contrario, ero già sposato quando apparve il libro, e oggi siamo a meno quattro anni dall’anno apocalittico (il ’1984′ è divenuto l’anno associato con tale minaccia grazie al libro di Orwell), e io ero contentissimo di poterlo vedere.

In questo capitolo, parlerò del libro, ma prima: chi era Blair/Orwell e perché scrisse questo libro?

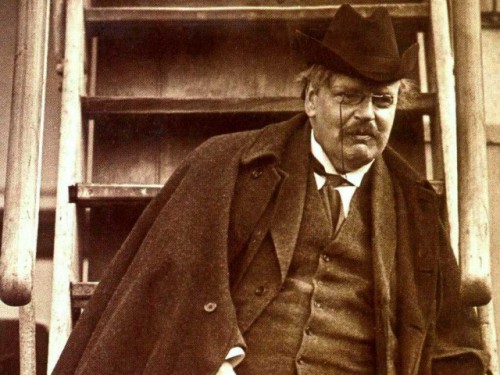

Blair nacque nel 1903 figlio di funzionario inglese, il padre era nel Indian civil service e Blair stesso visse la vita di un ufficiale imperiale inglese. Andò a Eton, servì in Birmania, ecc. Tuttavia, era sempre al verde per esser un “English gentleman” completo. Allora inoltre, non voleva passare il resto della sua vita alla scrivania; voleva essere uno scrittore. Ancora, si sentiva in colpa per la sua condizione di borghese medio-alto. Così negli anni ’20 fece quello che molti giovani americani fecero negli anni ’60. In breve divenne un cosiddetto ‘hippie‘ ante litteram. Viveva negli slum di Londra e Parigi, confondendosi e identificandosi con i vagabondi e i diseredati degli slum, cercando di sollevare la propria coscienza e, allo stesso tempo, di raccogliere materiale per i suoi primi libri. Divenne di sinistra, un socialista, combatté con i lealisti in Spagna negli anni ’30. Si ritrovò intrappolato nella lotta settaria tra fazioni di sinistra, e finché credeva in un socialismo da bravo inglese, era inevitabile che fosse nel lato perdente. Opposti a lui vi erano gli appassionati anarchici, sindacalisti, e comunisti spagnoli, che amaramente subivano il fatto che le necessità della lotta ai fascisti di Franco venissero sostituite dallo scontro fratricida. I comunisti, i meglio organizzati, vinsero e Orwell lasciò la Spagna, era convinto che lo avrebbero ucciso. Da allora fino alla morte, condusse una guerra letteraria contro i comunisti, determinato a vincere, con le parole, la battaglia che aveva perso sul terreno.

Durante la seconda guerra mondiale, dove venne scartato dal servizio militare, si associò con l’ala sinistra del British Labour party, ma non legò molto con il partito, poiché il suo blando socialismo gli sembrava fin troppo ben organizzato. Non era preoccupato, apparentemente, dal totalitarismo nazista, per lui c’era spazio solo per la guerra privata contro lo stalinismo. Perciò, quando il Regno Unito combatteva contro il nazismo, e l’URSS combatteva da alleato nella lotta e contribuì molto in vite umane perdute e in coraggio risoluto, Orwell scrisse “La fattoria degli animali” una satira della Rivoluzione Russa e di ciò che seguì, dipingendola come la rivolta di animali domestici contro i padroni umani. Completò “La fattoria degli animali” nel 1944 e ebbe problemi nel trovare un editore fin quando arrivò il momento buono per attaccare i sovietici. Appena finita la guerra, l’Urss divenne il nemico e “La fattoria degli animali” venne pubblicata. Venne accolta con ovazione e Orwell divenne sufficientemente ricco per andare in pensione e dedicarsi al suo capolavoro: 1984.

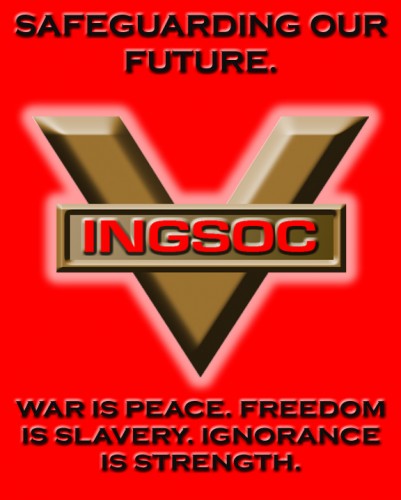

Il libro descrive una società come una super Russia stalinista mondiale in stile anni ’30, cioè come veniva dipinta dai settari di ultrasinistra. Altre forme di totalitarismo giocavano un ruolo secondario. Vi erano uno o due menzioni del nazismo e della inquisizione. All’inizio almeno due o tre riferimenti agli ebrei, avrebbero dovuto dimostrare la loro persecuzione, ma ciò sparisce subito e Orwell non vuole che il lettore identifichi i cattivi con i nazisti. L’immagine è lo stalinismo, e solo lo stalinismo.

Quando il libro apparve nel 1949, la guerra fredda era al culmine. Il libro divenne, perciò, popolare. Era una questione di patriottismo in occidente comprarlo e parlarne e, forse, persino leggerne una parte; è mia opinione che molta gente che lo ha comprato lo ha più discusso che letto, poiché è un libro ostico, statico, ripetitivo e didascalico. Fu molto popolare, all’inizio, presso le persone di destra, conservatrici, per essi era chiara la polemica contro l’Urss, e il quadro della vita lì mostrata nella Londra del 1984 era proprio quella immaginata dai conservatori nella Mosca del 1949.

Durante l’era di McCarthy negli USA, 1984 divenne sempre più popolare presso i liberals, poiché sembrava che gli USA dei primi anni ’50 scivolassero verso il controllo del pensiero e che tutti i mali che Orwell aveva descritto si stessero avverando. Quindi, in una prefazione di una edizione pubblicata in paperback dalla New American Library nel 1961, il psicoanalista e filosofo liberale Erich Fromm conclude così: “Il libro di Orwell è un potente allarme, e potrebbe essere una sfortuna se il lettore interpretasse 1984 come l’ennesima descrizione della barbarie stalinista, e non è detto che appaia, da noi, in quel modo.”

Anche quando lo stalinismo e il McCarthyismo scomparvero, sempre più statunitensi divennero consapevoli di come fosse divenuto “grande” il governo; di come fossero alte le tasse; di come la vita quotidiana e gli affari fossero sempre più regolati dalle leggi; di come l’informazione riguardante ogni fatto della vita privata entrasse nei documenti del governo, ma anche del sistema bancario privato.

1984, quindi, significava non più stalinismo, o dittatura, ma il semplice governo. Anche il paternalismo governativo sembrava ispirato a 1984 e la frase il “grande fratello ti vede” significava tutto ciò che era troppo grande per il controllo del singolo.

Non vi era solo un grande governo o un grande business che fosse sintomo del 1984, ma anche una grande scienza, un grande lavoro, un grande tutto. Infatti, la 1984-fobia penetrò nella coscienza di molti di coloro che non avevano letto il libro o avevano nozione del suo contenuto; ci si preoccupava di ciò che sarebbe accaduto entro il 31 Dicembre 1984. Una volta arrivato il 1985, con gli USA che erano ancora una realtà, e affrontava i molti problemi quotidiani, come esprimeremo la paura sugli aspetti della vita che ci riempiono di apprensione? Quale data inventeremo per sostituire il 1984?

Orwell non visse per vedere il proprio libro divenire un successo. Non vide il modo in cui fece del 1984 un anno che avrebbe perseguitato una intera generazione di statunitensi. Orwell morì di tubercolosi in un ospedale di Londra, nel gennaio 1950, pochi mesi dopo la pubblicazione del libro, all’età di 46 anni. Era consapevole della sua fine imminente, e l’amarezza l’aveva riversata nel libro.

B. La fantascienza di 1984

Molti pensano che 1984 sia un racconto di science fiction, ma l’unica cosa che supporti ciò e che 1984 sia ambientato nel futuro. Non è così! Orwell odia il futuro e la storia è più geografica che temporale.

La Londra in cui si svolge la storia si svolge a 30 anni di distanza, dal 1949 al 1984, e si svolge a migliaia di miglia a Est, a Mosca. Orwell immagina il Regno Unito colpito da una rivoluzione simile a quella Russa e che abbia attraversato tutti gli stadi dello sviluppo sovietico. Non prevede variazioni sul tema. I Sovietici ebbero una serie di purghe negli anni ’30, così il Ingsoc (English Socialism) ha avuto le sue purghe negli anni ’50. I Sovietici convertirono uno dei loro rivoluzionari, Leon Trotsky, in un nemico, e al contrario, il suo oppositore Josip Stalin, in un eroe. L’Ingsoc, tuttavia, converte uno dei suoi rivoluzionari, Emmanuel Goldstein, in un nemico, e il suo oppositore, con baffi come Stalin, in un eroe. Non è difficile fare piccole modifiche, Goldstein, come Trotsky, “dalla faccia di ebreo, con la grande cresta di capelli bianchi e la barbetta di capra“. Orwell apparentemente non vuole confondere il tema dando un nome diverso a Stalin e così lo chiama semplicemente ‘Grande Fratello‘.

All’inizio della storia, è chiaro che la televisione (appena nata al momento della stesura del libro) serviva come continuo mezzo di indottrinamento del popolo, che non può essere spenta. (e, apparentemente, in una Londra fatiscente, in cui nulla funziona, tale dispositivo è sempre acceso.)

Il grande contributo orwelliano alla tecnologia del futuro é che la televisione funziona nei due sensi, e la gente che è forzata a vederla può essere veduta e ascoltata e essere sottoposta a una costante supervisione anche quando dorme o è in bagno. Ecco, perciò, il significato della frase ‘il Grande Fratello ti vede‘. Questo è il peggior mezzo per controllare tutti. Avere una persona che è sotto controllo ogni momento significa averne un’altra che la guarda sempre (almeno nella società orwelliana) e farebbe assai poco, per questo vi è un grande sviluppo dell’arte della recitazione e dell’espressione mimica. Una persona non può guardare più di un’altra in piena concentrazione, e può solo farlo in un breve periodo di tempo, prima che l’attenzione scemi. Posso testimoniare, in breve, che dovrebbero esserci almeno cinque persone per osservarne una. E certo, gli osservatori stessi sarebbero osservati, poiché nessuno nel mondo orwelliano è libero dal sospetto. Perciò, il sistema di oppressione attraverso la TV interattiva non può funzionare.

Orwell stesso lo capisce, limitando il lavoro ai membri del partito. I ‘proles‘ (proletariato), verso cui Orwell non può nascondere il suo atteggiamento borghese inglese, sono largamente lasciati a presentarsi come subumani. (A un certo punto nel libro, dice che ogni prolet che mostra abilità è ucciso – come facevano gli spartani con gli iloti 25 secoli fa.) Inoltre, vi è un sistema di spie volontarie in cui i bambini controllano i genitori e i vicini si spiano tra di loro. Non è possibile che funzioni bene, poiché se tutti spiano tutti, il resto verrebbe abbandonato.

Orwell non era capace di concepire i computer o i robot, o di mettere tutti sotto il controllo non umano. I nostri computers arriva a farlo con l’IRS (servizio immigrazione, NdC), nel credito bancario e così via, ma nel 1984 la cosa non ci coinvolge direttamente, tranne che nella più fervida immaginazione. Computer e tirannia non vanno necessariamente mano nella mano. I Tiranni hanno lavorato bene senza i computer (vedi i nazisti) e le nazioni più computerizzate oggi, sono le meno tiranniche (ancora oggi è così? NdC).

Orwell era privo della capacità di vedere o inventare dei piccoli cambiamenti. Il suo eroe trova difficile nel mondo di 1984 avere lacci per scarpe o lame per rasoi. Così il vero mondo degli anni ’80, utilizza mocassini e rasoi elettrici. Allora, anche Orwell aveva la fissazione tecnofobica che ogni progresso tecnologico è una scorciatoia. Perciò, l’eroe quando scrive, “mette la penna nel calamaio e ne risucchia l’inchiostro. Fa così perché sente che la bella carta color crema sia destinata a essere scritta con un vero pennino invece che essere graffiata con una penna a inchiostro“. Presumibilmente, la “penna a inchiostro” è la penna a sfera che era appena stata introdotta quando 1984 venne scritto. Ciò significa che Orwell descrive che qualcosa sia scritta con un vero pennino ma rimane graffiata dalla penna a sfera. Ciò è, tuttavia, precisamente il contrario del vero. Se sei abbastanza vecchio da ricordare che i pennini graffiano fragorosamente e si sa che la penna a sfera non lo fa.

Tutto questo non è science fiction, ma una nostalgia distorta del passato che non c’è mai stato. Sono sorpreso che Orwell si sia fermato al pennino e che non abbia fatto usare a Winston una grossa penna d’oca. Né Orwell era particolarmente previdente negli aspetti strettamente sociali del futuro che presenta, con il risultato che il mondo orwelliano di 1984 è incredibilmente arcaico comparato con quello vero degli anni ’80. Orwell non immagina nuovi vizi, al contrario. Egli era tutto gin e tabacco, e parte dell’orrore del suo quadro di 1984 è l’eloquente descrizione della bassa qualità del gin e del tabacco. Non prevedeva nuove droghe, non la marijuana, né gli allucinogeni sintetici. Non un aspetto della s.f. dello scrittore è precise e esatto nella sua previsione, ma certamente ci si sarebbe aspettato che inventasse qualche differenza.

Nella sua disperazione (o rabbia), Orwell dimentica le virtù umane. Tutti i caratteri sono, in un modo o nell’altro, deboli o sadici, sleali, stupidi o repellenti. Questo dovrebbe essere il modo in cui la gent,e o come Orwell vuole indicare, siano sotto la tirannia, ma mi sembra che sotto le peggiori tirannie, vi siano uomini e donne coraggiosi che affrontano i tiranni fino alla morte e che tali personalità storiche abbiano illuminato l’oscurità circostante. Solo per questo 1984 non assomiglia al vero mondo degli anni ’80. Né prevede alcuna differenza nel ruolo delle donne o nella debolezza dello stereotipo femminile del 1949. Vi sono solo due caratteri di donna di qualche importanza. Una forte donna ‘prole’ senza cervello che è sempre lavandaia, che canta sempre canzoni popolari con parole del tipo famigliare negli anni ’30 e ’40 (a cui Orwell descrive fastidiosamente come ‘spazzatura’, in piena e beata assenza di anticipazione dell’hard rock).

L’altra è l’eroina, Julia, che è sessualmente promiscua (ma almeno mostra coraggio per il suo interesse nel sesso) ed è d’altronde senza cervello. Quando l’eroe, Winston, legge il suo libro che spiega la natura del mondo orwelliano, lei risponde addormentandosi, ma visto che Winston legge in modo estremamente soporifero, ciò è una buona indicazione del buon senso di Julia piuttosto che del contrario.

In breve, se 1984 deve essere considerato science fiction, allora è pessima science fiction.

C. Il governo di 1984

Il 1984 di Orwell è il ritratto di un governo totalitario, e ciò aiuta a comprendere la nozione del ‘big government’ assai eclettico. Dobbiamo ricordare, che il mondo dei tardi anni ’40, quando Orwell scrive il libro, vi era un solo vero e cattivo “big governments” con un vero tiranno-individuale il cui desiderio, anche se ingiusto crudele e vizioso, era legge. Inoltre sembrava un tiranno irremovibile eccetto che dalla forza esterna.

Benito Mussolini dell’Italia, dopo 21 anni di dominio assoluto, venne rovesciato, ma solo a causa della sua sconfitta in guerra. Adolf Hitler della Germania, dittatore assai più forte e brutale, dominò con pugno di ferro per dodici anni, e anche se sconfitto, non venne abbattuto dall’interno. Sebbene l’area che dominava si restringeva e gli eserciti nemici lo circondavano a est e a ovest, rimaneva dittatore assoluto nell’area da lui controllata, anche quando era solo nel bunker in cui si suicidò. Finchè si tolse di mezzo, nessuno poté abbatterlo. (Vi furono dei complotti contro di lui, certo, ma fallirono sempre, grazie, spesso, alla fortuna, che sembrava incredibile solo pensando a qualcuno come lui.)

Orwell, tuttavia, non badava a Mussolini o Hitler. Il suo nemico era Stalin, e al momento in cui venne pubblicato 1984, Stalin governava l’URSS da 25 anni ininterrotti, era sopravvissuto a una guerra tremenda in cui la sua nazione soffrì perdite enormi e ora era più forte che mai. A Orwell, ciò sembrava che né il tempo né la fortuna potessero abbattere Stalin, ma che sarebbe vissuto per sempre, aumentando di forza. Era così che Orwell presentava il Grande Fratello. Certo, non era vero. Orwell non vise abbastanza da vedere la morte di Stalin, tre anni dopo la pubblicazione di 1984, e non molto dopo il suo regime fu denunciato come dittatura – indovinate da chi? – dalla leadership sovietica. L’URSS è ancora URSS, ma non è stalinista, e i nemici dello stato non sono più fucilati (Orwell diceva ‘vaporizzati‘ invece, ma tale piccola differenza era tutto quello che sapeva fare) pratica presto abbandonata. Anche quando morì Mao Tse-tung in Cina, e mentre egli stesso non venne denunciato, i suoi più stretti collaboratori, la “Banda dei quattro“, vennero subito rimossi dallo stato di divinità, e ora la Cina è rimasta Cina, ma non è più maoista. Franco della Spagna morì nel suo letto e fino al suo ultimo respiro, rimase il leader indiscusso per quasi 40 anni, subito dopo il suo ultimo respiro, il fascismo sparì subito dalla Spagna, così in Portogallo dopo al morte di Salazar.

In breve, Grande Fratello muore, o dovrebbe farlo, e quando muore, il governo muta sempre in senso moderato. Non si sa come i nuovi dittatori si sentano, ma dovranno morire, anche. Alla fine nei veri anni ’80 sappiamo i dittatori passano e che il “Grande Fratello“ non è una minaccia reale.

Se nessun governo, infatti, degli anni ’80, sembra così pericoloso. L’avanzata della tecnologia concede nuove armi potenti – esplosivi, mitragliatrici, auto veloci in mano a terroristi urbani che possono rapire, sequestrare, uccidere e prendere ostaggi con impunità mentre i governi sono più o meno aiuti privi di aiuto. Inoltre la immortalità del Grande Fratello, che Orwell presenta come i due modi altri modi di mantenere una dittatura eterna.

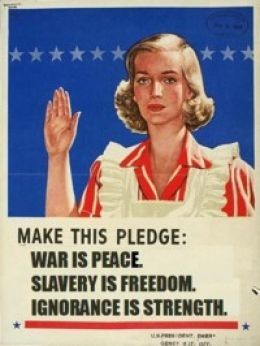

Primo -presenta qualcuno o qualcosa da odiare. Nel mondo orwelliano era Emmanuel Goldstein da odiare e che era costruito e orchestrato in funzione di masse robotizzate. Nulla di nuovo, certo. Ogni nazione nel mondo ha usato i vicini allo scopo di odiare. Tale tipo di cosa è facilmente gestito e emerge come la seconda natura dell’umanità che meraviglia perché vi sono gli odi guidati organizzati nel mondo orwelliano. Necessita poca psicologia delle masse per fare odiare gli Arabi con gli Israeliani, Greci con i Turchi e cattolici Irlandesi con i protestanti Irlandesi – e viceversa in ogni caso. Per essere sicuri i nazisti organizzavano incontri di massa da delirio a cui ogni partecipante sembrava unirsi, ma non vi erano effetti permanenti. Una volta arrivata la guerra sul suolo Germanico, i tedeschi si arrendevano e non hanno mai più detto Sieg-Heil nella loro vita.

Secondo – riscrivere la storia. Quasi ogni individuo che incontriamo in 1984 ha come lavoro, la rapida riscrittura del passato, il riaggiustamento delle statistiche, la revisione dei giornali, con tutti preoccupati di fare attenzione al passato comunque. Tale preoccupazione orwelliana per le minuzie storiche è tipica del settario politico che sempre riporta ciò che è stato detto sin passato per provare a chiunque dell’altro lato che è sempre citato qualcosa che è sttao detto o fatto dell’avversario. Coma sa ogni politico, nessuna prova di qualsiasi tipo è mai richiesto. È solo necessario fare una dichiarazione – qualsiasi – per avere una audience che vi crede. Nessuno vedrà la bugia rispetto ai fatti e, se lo fa, non crederanno ai fatti.

Pensate che i tedeschi nel 1939 fingessero di credere che i polacchi gli avessero attaccati e iniziando la Seconda Guerra Mondiale? No! Quando gli si disse che era così essi vi credettero come io credo che essi attaccarono i polacchi. Sicuro, i sovietici pubblicarono nuove edizioni della loro Enciclopedia in cui politici che avevano lunghe citazioni nelle prime edizioni, venivano all’improvviso cancellati totalmente, e ciò è senza dubbio il germe della nozione orwelliana, ma la possibilità di portare ciò al livello di descritto in 1984 sembra nullo – non perché è oltre la malvagità umana, ma perché non è necessaria.

Orwell presenta la ‘Neolingua‘ come organo della repressione – la conversione dell’inglese in uno strumento limitato e abbreviato dove il vocabolario reale dei dissensi sparisce. Parzialmente acquisì la nozione dell’indubbia abitudine dell’abbreviare. Diede degli esempi: la ‘Internazionale Comunista‘ divenne ‘Comintern‘ e ‘Geheime Staatspolizei‘ divenne ‘Gestapo‘, ma non è una invenzione del moderno totalitarismo. ‘Vulgus mobile‘ divenne ‘mob‘; ‘taxi cabriolet‘ divenne ‘cab’; ‘quasi-stellar radio source’ divenne ‘quasar’; ‘light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation’ divenne ‘laser’ e così via. Non ci sono segnali che la compressione della lingua renda più debole il modo di esprimere.

In realtà l’offuscamento politico tende a usare molte parole invece che poche, lunghe invece che corte, a estendere invece che a ridurre. Ogni leader poco istruito o dalla intelligenza limitata si nasconde dietro una esuberante e inebriante loquacità. Quindi, quando Winston Churchill suggerisce lo sviluppo di un ‘Inglese Basico’ come lingua internazionale (indubbiamente similmente alla “Neolingua“), la suggestione era forte. Non possiamo, tuttavia, avvicinarci alla Neolingua nella sua forma condensata, ma abbiamo già una Neolingua nella sua forma estesa e sempre l’avremo. Abbiamo un gruppo di giovani tra noi che dice cose come “Vabbene, uomo, sai, è come prenderli tutti assieme, sai, uomo, penso, come sai tu” e così per cinque minuti quando la parola che i giovani cercano è il loro ‘Huh?‘ Perciò, tuttavia, non è Neolingua, è sempre stato così da noi. È qualcosa che in Veterolingua è chiamato ‘mancanza di articolazione’ e non è ciò che Orwell aveva in mente.

D. La situazione internazionale di 1984

Sebbene Orwell sembri, di massima, essersi inesorabilmente bloccato nel mondo del 1949, in un aspetto si mostra assai previdente, cioè la previsione della tripartizione del mondo negli anni ’80.

Il mondo internazionale di 1984 è un mondo di tre superpotenze: Oceania, Eurasia e Estasia – e che combacia, assai rozzamente, con le tre attuali superpotenze degli anni ’80: gli USA, l’URSS e la Cina. (Potremmo anche fare con USA, Unione Europea e Cina degli anni ’90; NdC)

L’Oceania è la combinazione di USA e Impero inglese, chi è stato un ufficiale imperiale civile, non avverte che l’impero inglese stava esalando l’ultimo respiro nei tardi anni ’40 e stava per dissolversi. Sembra supporre, in effetti, che l’impero inglese sia il membro dominante della coalizione anglo-americana. Alla fine, L’intera azione si svolge a Londra e frasi come gli ‘USA’ e ‘americani’ sono rare, se mai, menzionate. Ma, ciò è assai tipico nei racconti di spie inglesi in cui, fin dalla seconda guerra mondiale, il Regno Unito (adesso l’ottava potenza militare economica del Mondo) appare come la grande avversaria dell’URSS, o della Cina, o di qualche inventata cospirazione internazionale, con gli USA mai menzionata o ridotta a piccola comparsa con la cortese partecipazione di qualche agente della CIA.

Eurasia è, naturalmente, l’URSS, cui Orwell fa assorbire tutto il continente Europeo. Eurasia, inoltre, include oltre all’Europa, la Siberia, e la sua popolazione è per 95 % europea in ogni modo. Quindi, Orwell descrive gli Eurasiani come ‘uomini dall’aspetto robusto con visi asiatici privi di espressione‘. Orwell viveva in un periodo in cui gli ‘Europei‘ e gli ‘Asiatici‘ erano rispettivamente l”eroe‘ e il ‘cattivo‘, era impossibile attaccare l’URSS con spontaneità se non pensandola come ‘Asiatica’. Ciò avvenne sotto l’inebriante Neolingua Orwelliana detta ‘doppio-pensiero‘, qualcosa che Orwell, come ogni uomo ritiene, buona cosa. Certo, potrebbe darsi che Orwell non pensi all’Eurasia, o all’URSS, ma la sua grande ‘bestia nera’ è Stalin. Stalin era un georgiano, e la Georgia, che si estende nel Caucaso meridionale, geograficamente è in Asia. Eastasia è, certo, la Cina e varie nazioni tributarie. Qui fa una profezia. Al momento della stesura di 1984, i comunisti cinesi non avevano il controllo del paese e molti (gli USA soprattutto) ritenevano che l’anticomunista, Chiang Kai-shek, avesse il controllo. Una volta che i comunisti ottennero il potere, divenne credo accettato degli occidentali che i cinesi fossero sotto il controllo dei sovietici e che la Cina e l’URSS formassero un blocco monolitico comunista.

Orwell no solo previde la vittoria comunista (vedeva la vittoria dovunque, infatti) ma inoltre previde che Russia e China non avrebbero formato una potenza monolitica ma sarebbero stati nemici mortali. In tale caso, è stata la sua esperienza di settario di sinistra ad aiutarlo. Non aveva le superstizioni di destra riguardo alla sinistra come unificazione di indistinti cattivi. Sapeva che avrebbero combattuto tra loro spietatamente sopra i punti assai controversi della dottrina come i più pii cristiani. Inoltre previde uno stato permanente di guerra tra le tre potenze; una condizione di permanente mutazione delle sempre instabili alleanze, ma sempre due contro il più forte. Questa era il vecchio sistema di “equilibrio del potere” presente fin dall’antica Grecia, nell’Italia medievale, e nella prima Europa moderna.

L’errore di Orwell risiede nel pensare che vi fosse una guerra per mantenere il controllo dell’equilibrio. In effetti, nella parte più risibile del libro, presenta la guerra come mezzo per consumare le risorse e la produzione mondiale e quindi mantenere la stratificazione sociale con classi superiori, medie e inferiori. (ciò suona come un vera spiegazione di sinistra della guerra come risultato di una cospirazione attuata con grande difficoltà.) Nei fatti odierni, le decadi dal 1945 sono state segnate dall’assenza di guerre rispetto ai decenni precedenti. Vi sono state guerre locali a profusione, ma non una generale. Ma la guerra non è ritenuta un mezzo disperato per consumare le risorse del mondo. Ciò può essere fatto con altri metodi, come l’incremento senza fine della popolazione e dell’uso dell’energia, mai considerate da Orwell. Orwell non prevede alcuni significativo mutamento economico che sono stati attuati dopo la fine della seconda guerra mondiale. Non prevede il ruolo del petrolio o del declino della sua disponibilità o l’aumento del suo prezzo o l’incremento della potenza di quelle nazioni che lo controllano. Non ricordo alcun riferimento al ‘petrolio‘. Ma forse in ciò è Orwell abbastanza vicino da prevederlo, se sostituiamo

‘guerra fredda‘ con ‘guerra‘. Vi sono stati eventi, in effetti, da continuare, più o meno, la ‘guerra fredda‘ che serviva a mantenere l’occupazione elevata e a risolvere a breve termine i problemi economici (al costo di crearne di assai più grandi a lungo termine). E questa Guerra Fredda è sufficiente da esaurire le risorse. Inoltre, l’alleanza mutevole, come previsto da Orwell è assai vicina alla realtà. Quando gli USA sembravano potentissimi, URSS e Cina erano ferocemente anti-statunitensi, e si allearono. Quando la potenza USA diminuì, l’URSS e Cina si divisero. E ognuno si contrappose egualmente contro gli altri due. Allora, quando l’URSS apparve divenire abbastanza potente, si ebbe una alleanza tra USA e Cina, e cooperarono per contrastare l’URSS, e parlare moderatamente ognuno dell’altro.

In 1984 ogni cambio di alleanza sfociava in una orgia di storia riscritta. In realtà, tale follia non era necessaria. IL pubblico scivolava facilmente da un punto all’altro, accettando il cambio di circostanza senza alcun problema per il passato. Invece, i giapponesi, negli anni ’50, cambiarono da cattivi senza speranza in amici, mentre i cinesi passarono nella direzione opposta, senza aver commesso nessuna Pearl Harbour. Nessuno ci fece caso, per buona stupidità. Orwell ha volontariamente dimenticato l’uso della bomba atomica nella guerra tra le tre potenze, sicuro che tali bombe non sarebbero state usate nelle guerre dopo il 1945. Ciò, tuttavia, a causa che le sole grandi potenze nucleari USA e URSS, hanno impedito la guerra tra di loro. Se ci fosse una guerra adesso, assai dubbio che le parti non credano, infine, necessario premere il bottone. In ciò, Orwell manca, forse, di poco la realtà. Londra, tuttavia, ha sofferto attacchi di missili, cosa che richiama le armi V-1 o V-2 del 1944, e la città è in una bolgia stile 1945. Orwell non può rendere 1984 assai differente dal 1944 in tale aspetto. Orwell, infatti, rende chiaro che in 1984, il comunismo universale delle tre superpotenze ha soffocato la scienza e ridotto il suo uso tranne che per le necessità della guerra. Non vi sono domande su quale nazione investe di più nella scienza dove le applicazioni per la guerra sono chiare, né vi è modo di porre domande sulla separazione delle applicazioni per la guerra da quelle per la pace.

La Scienza è una unità, e ogni cosa può essere concepita in relazione alla guerra e alla distruzione. La Scienza, inoltre, non è stata soffocata ma continua non solo negli USA e nell’Europa Occidentale e Giappone, ma anche in URSS e in Cina. I progressi della scienza sono numerosi, ma si può pensare ai laser e ai computer come armi dalle infinite applicazioni pacifiche.

Insomma: George Orwell in 1984 era, secondo me, impegnato in una guerra privata con lo stalinismo, piuttosto che cercare di prevedere il futuro. Non diede alla scienza alcuna plausibile funzione prevedibile in futuro, e oggi, in ogni caso il mondo di 1984 non è correlato al mondo reale degli anni ’80. Il mondo può essere comunista, me non nel 1984, che per qualcuno non è una vera tarda data; o dove sembri che la civiltà stia per essere distrutta. Se accadesse, tuttavia, accadrà in modo diverso da quello descritto in 1984 e se tentate di prevenirne l’eventualità immaginando che 1984 sia accurata, allora dovrete difendervi dagli assalti provenienti da direzioni sbagliate e perderete.

Traduzione Alessandro Lattanzio

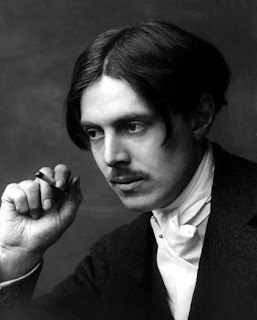

In September 1915 Lawrence’s novel The Rainbow, one of his major works, was published by Methuen. By November it had been banned by court order, largely due to Lawrence’s brief (and, by today’s standards, extremely tame) depiction of a lesbian affair. The following year Lawrence finished what is arguably his greatest novel, Women in Love. However, owing to the notoriety of The Rainbow as well as to Women in Love’s much more frank depiction of sexuality, he could not find a publisher for the novel until 1920. Disgusted by his treatment at the hands of his fellow countrymen, Lawrence moved himself and his wife Frieda to Sicily that year, thereby beginning a long sojourn abroad that would take them to Sardinia, Ceylon, Australia, California, and New Mexico.

In September 1915 Lawrence’s novel The Rainbow, one of his major works, was published by Methuen. By November it had been banned by court order, largely due to Lawrence’s brief (and, by today’s standards, extremely tame) depiction of a lesbian affair. The following year Lawrence finished what is arguably his greatest novel, Women in Love. However, owing to the notoriety of The Rainbow as well as to Women in Love’s much more frank depiction of sexuality, he could not find a publisher for the novel until 1920. Disgusted by his treatment at the hands of his fellow countrymen, Lawrence moved himself and his wife Frieda to Sicily that year, thereby beginning a long sojourn abroad that would take them to Sardinia, Ceylon, Australia, California, and New Mexico. In Fantasia of the Unconscious Lawrence writes, “In sex we have our basic, most elemental being.”[8] Further, he declares that the procreative purpose of sex is “just a side-show.”[9] Lawrence rejects the reductive, scientific understanding of sex; part and parcel of the scientific will to nullify beauty and mystery and to make everything mundane and “practical.”

In Fantasia of the Unconscious Lawrence writes, “In sex we have our basic, most elemental being.”[8] Further, he declares that the procreative purpose of sex is “just a side-show.”[9] Lawrence rejects the reductive, scientific understanding of sex; part and parcel of the scientific will to nullify beauty and mystery and to make everything mundane and “practical.” Interestingly, I believe that Lawrence derives the idea of “cells” being male or female from Otto Weininger’s Sex and Character, a text he was definitely familiar with. Weininger writes: “every cell of the organism . . . has a sexual character.” And: “In a male every part, even the smallest, is male, however much it may resemble the corresponding part of a female, and in the latter, likewise, even the smallest part is exclusively female.”[14]

Interestingly, I believe that Lawrence derives the idea of “cells” being male or female from Otto Weininger’s Sex and Character, a text he was definitely familiar with. Weininger writes: “every cell of the organism . . . has a sexual character.” And: “In a male every part, even the smallest, is male, however much it may resemble the corresponding part of a female, and in the latter, likewise, even the smallest part is exclusively female.”[14]

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

When the ban on D.H. Lawrence’s controversial novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, was finally lifted in 1960 it was a watershed moment for censorship in Britain. But many assume it was only Lawrence’s novels that suffered at the hands of the censors.

When the ban on D.H. Lawrence’s controversial novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, was finally lifted in 1960 it was a watershed moment for censorship in Britain. But many assume it was only Lawrence’s novels that suffered at the hands of the censors.

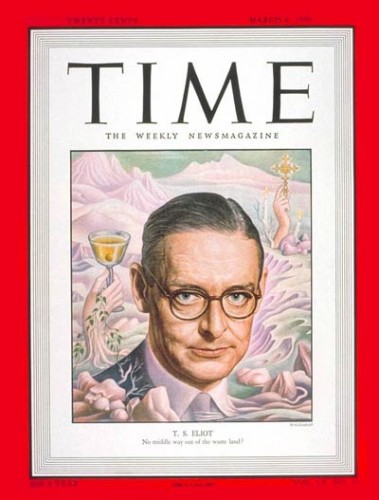

Wenn Eliot seine Glaubenslehre verteidigt, läuft seine Darlegung Cunningham zufolge eher „auf einen soziologischen als einen theologischen Standpunkt“ hinaus. Der Dichter verstand sie als Bestandteil der Idee einer „universalen Kirche“ im Kontext der römischen und orthodoxen Konfessionen. Nach dem strengen Katholiken Cuningham scheiterte das Verfahren in dem Maße, dass Eliot von einer selbstbezogenen Vorstellung ausging, ohne in einer wahren religiösen Tradition verankert zu sein.

Wenn Eliot seine Glaubenslehre verteidigt, läuft seine Darlegung Cunningham zufolge eher „auf einen soziologischen als einen theologischen Standpunkt“ hinaus. Der Dichter verstand sie als Bestandteil der Idee einer „universalen Kirche“ im Kontext der römischen und orthodoxen Konfessionen. Nach dem strengen Katholiken Cuningham scheiterte das Verfahren in dem Maße, dass Eliot von einer selbstbezogenen Vorstellung ausging, ohne in einer wahren religiösen Tradition verankert zu sein.

Ich will direkt an Kubitscheks

Ich will direkt an Kubitscheks

Né le 19 septembre 1911, William Golding peut être considéré comme le grand marginal de la littérature anglaise contemporaine. Le vécu existentiel, pour lui, a été le plus intense pendant la seconde guerre mondiale, où il a servi dans la marine —Golding était présent quand le Bismarck a coulé et au moment du débarquement anglo-américain de Normandie. Il a pris conscience de ce que les hommes pouvaient mutuellement s’infliger. Les expériences de la guerre ont conduit Golding, qui, avant les hostilités, croyait encore au perfectionnement de l’homme en tant qu’être social, à penser “que l’homme produit de la méchanceté comme les abeilles produisent du miel”. Le produit littéraire de cette grande désillusion est un roman, paru en 1954, et intitulé “Lord of the Flies” (en français: “Sa Majesté des Mouches”). Ce roman a permis à Golding d’acquérir la célébrité car il est devenu un succès international.

Né le 19 septembre 1911, William Golding peut être considéré comme le grand marginal de la littérature anglaise contemporaine. Le vécu existentiel, pour lui, a été le plus intense pendant la seconde guerre mondiale, où il a servi dans la marine —Golding était présent quand le Bismarck a coulé et au moment du débarquement anglo-américain de Normandie. Il a pris conscience de ce que les hommes pouvaient mutuellement s’infliger. Les expériences de la guerre ont conduit Golding, qui, avant les hostilités, croyait encore au perfectionnement de l’homme en tant qu’être social, à penser “que l’homme produit de la méchanceté comme les abeilles produisent du miel”. Le produit littéraire de cette grande désillusion est un roman, paru en 1954, et intitulé “Lord of the Flies” (en français: “Sa Majesté des Mouches”). Ce roman a permis à Golding d’acquérir la célébrité car il est devenu un succès international.  Dans “Lord of the Flies” —le titre, rappellons-le, est une traduction littérale du concept hébraïque de “Belzébuth”, le “Seigneur des Mouches”— le tête de porc fichée sur un pieu, que les “chasseurs” offrent en sacrifice pour conjurer le danger d’un “monstre” qui les menacerait, symbolise le Mal. En voyant cette tête de porc, entourée d’une dégoûtante nuée de mouches, Simon, qui finira martyr, reconnaît que l’homme lui-même est ce “monstre”, une créature déchue.

Dans “Lord of the Flies” —le titre, rappellons-le, est une traduction littérale du concept hébraïque de “Belzébuth”, le “Seigneur des Mouches”— le tête de porc fichée sur un pieu, que les “chasseurs” offrent en sacrifice pour conjurer le danger d’un “monstre” qui les menacerait, symbolise le Mal. En voyant cette tête de porc, entourée d’une dégoûtante nuée de mouches, Simon, qui finira martyr, reconnaît que l’homme lui-même est ce “monstre”, une créature déchue.